Academic reading practice test 37 Going bananas , Travel Books , Coastal Archaeology of Britain

Please download the PDF file offline and give exam for any information contact at [email protected]

ieltsfever-academic-reading-practice-test-37-pdf

answers-ieltsfever-academic-reading-practice-test-37-pdf

you can also download in zip file password= “ieltsfever.com”

ieltsfever-academic-reading-practice-test-37-ZIP

READING PASSAGE 1 Questions 1 – 13

You should spend about 20 minutes on Questions 1 – 13 which are based on Reading Passage 1 below.

Going bananas

The banana is among the world’s oldest crops. Agricultural scientists believe that the first edible banana was discovered around 10,000 years ago. It has been at an evolutionary standstill ever since it was first propagated in the jungles of South-East Asia at the end of the last Ice Age. Normally the wild banana, a giant jungle herb card Musa acuminata, contains a mass of hard seeds that make the fruit virtually inedible. But now-and-then, hunter-gatherers must have discovered rare mutant plants that produced seamless, edible fruits. Geneticists now know that the vast majority of these soft-fruited plants resulted from genetic accidents that gave their cells three copies of each chromosome instead of the usual two. This imbalance prevents seeds and pollens from developing normally, rendering the mutant plants sterile. And that is why some scientists believe the worst – the most popular fruit could be doomed. It lacks the genetic diversity to fight off pests and diseases that are invading the banana plantations of Central America and smallholdings of Africa and Asia alike.

In some ways, the banana today resembles the potato before blight brought famine to Ireland a century and a half ago. But it holds a lesson for other crops too, says Emile Frison, top banana at the International Network for the Improvement of Banana and Plaintain in Montpellier, France. The state of the banana, Frison warns, can teach a broader lesson: the increasing standardization of food crops around the world is threatening their ability to adapt and survive.

The first Stone Age plant breeders cultivated these sterile freaks by replanting cuttings from their stems. And the descendants of those original cuttings are the bananas we still eat today. Each is a virtual clone, almost devoid of genetic diversity. And that uniformity makes it ripe for disease like no other crop on Earth. Traditional varieties of sexually reproducing crops have always had a much broader genetic base, and the genes will recombine in new arrangements in each generation. This gives them much greater flexibility in the evolving response to disease – and far more genetic resources to draw on in the face of an attack. But that advantage is fading fast, as growers increasingly plant the same few high-yielding varieties. Plant breeders work feverishly to maintain resistance in these standardized crops. Should these efforts falter, yields of even the most productive crop could swiftly crash. “When some pests or disease comes along severe epidemics can occur,” says Geoff Hawtin, director of the Rome-based International Plant Genetic Resources Institute.

The banana is an excellent case in point. Until the 1950s, one variety, the Gros Michel, The banana is an excellent case in point. Until the 1950s, one variety, the Gros Michel, dominated the world’s commercial business. Found by French botanists in Asia in the 1820s, the Gros Michel was by all accounts a fine banana, richer and sweeter than today’s standard banana, and without the latter’s bitter aftertaste when green. But it was vulnerable to a soil fungus that produced a wilt known as Panama disease. “Once the fungus gets into the soil, it remains there for many years. There is nothing farmers can do. Even chemical spraying wont get rid of it,” says Rodomiro Ortiz, director of the international Institute for Tropical Agriculture in Ibadan, Nigeria. So plantation owners played a running game, abandoning infested fields and moving to “clean” land – until they ran out of clean land in the 1950s and had to abandon the Gros Michel. Its successor, and still the reigning commercial king, is the Cavendish banana, a 19th century British discovery from southern China. The Cavendish is resistance to Panama disease and, as a result, it literally saved the international banana industry. During the 1960s, it replaced the Gros Michel on supermarket shelves. If you buy a banana today, it is almost certainly a Cavendish. But even so, it is a minority in the world’s banana crop.

Half a billion people in Asia and Africa depend on bananas. Bananas provide the largest source of calories and are eaten daily. Its name is synonymous with food. But the day of reckoning maybe coming for the Cavendish and its indigenous kin. Another fungal disease, Black Sigatoka – which causes brown wounds on leaves and premature fruit ripening – cuts fruit yields by 50 to 70% and reduces the productive life of banana plants from 30 years to as little as two or three. Commercial growers keep Sigatoka at bay by a massive chemical assault. 40 sprayings of fungicide a year is typical. But even so, diseases such as Black Sigatoka are getting more and more difficult to control. “As soon as you bring in a new fungicide, they develop resistance,” says Frison. “One thing we can be sure of is that the Sigatoka won’t lose in the battle.” Pool farmers, who cannot afford chemicals, have it even worse. They can do little more than watch their plants die. “Most of the banana trees in Amazonia have already been destroyed by the disease” says Luadir Gesparotto, Brazil’s leading banana pathologist with the government research agency EMBRAPA. Production is likely to fall by 70% as the disease spreads, he predicts. The only option would be to find a new variety.

But how? Almost all edible varieties are susceptible to the diseases, so growers cannot simply change to a different banana. With most crops, such a threat would unleash an army of breeders, scouring the world for resistant relatives whose traits they can breed into commercial varieties. Not so with the banana. Because all edible varieties are sterile, bringing in new genetic traits to help cope with pests and dis-eases is nearly

impossible. Nearly, but not totally. Very rarely, a sterile banana will experience a geneticimpossible. Nearly, but not totally. Very rarely, a sterile banana will experience a geneticaccident that allows an almost normal seed to develop, giving breeders a tiny windowfor improvement. Breeders at the Honduran Foundation of Agricultural Research havetried to exploit this to create disease-resistant varieties. Further backcrossing with wildbananas yielded a new seedless banana resistant to both black Sigatoka and Panama disease.

Neither Western supermarket consumers nor peasant growers like the new hybrid. Some accuse it of tasting more like an apple than a banana. Not surprisingly, the majority of plant breeders have until now turned their backs on the banana and got to work on easier plants. And commercial banana companies are now washing their hands of the whole breeding effort, preferring to fund a search for new fungicides instead. “We supported a breeding programme for 40 years, but it wasn’t able to develop an alternative to Cavendish. It was very expensive and we got nothing back,” says Ronald Romero, head of research at Chiquita, one of the Big Three companies that dominate the international banana trade.

Last year, a global consortium of scientists led by Frison announced plans to sequence the banana genome within five years. It would be the first edible fruit to be sequenced. Well, almost edible. The group will actually be sequencing inedible wild bananas from East Asia because many of these are resistant to black Sigatoka. If they can pinpoint the genes that help these wild varieties to resist black Sigatoka, the protective genes could be introduced into laboratory tissue cultures of cell from edible varieties. These could then be propagated into new, resistant plants and passed on to farmers.

It sounds promising, but the big banana companies have, until now, refused to get involved in GM research for fear of alienating their customers. “Biotechnology is extremely expensive and there are serious questions about consumer acceptance,” says David McLaughlin, Chiquita’s senior director for environmental affairs. With scant funding from the companies, the banana genome researchers are focusing on the other end of the spectrum. Even if they can identify the crucial genes, they will be a long way from developing new varieties that smallholders will find suitable and affordable. But whatever biotechnology’s academic interest, it is the only hope for the banana. Without it, banana production worldwide will head into a tailspin We may even see the extinction of the banana as both a lifesaver for hungry and impoverished Africans and as the most popular product on the world’s supermarket shelves.

Questions 1-3

Complete the sentences below with NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS from the

passage. Write your answers in boxes 1-3 on your answer sheet.

1. The banana was first eaten as a fruit by humans almost………years ago.

2. Bananas were first planted in ………

3. The taste of wild bananas is adversely affected by its………..

Questions 4-10

Look at the following statements (Questions 4-10) and the list of people below.

Match each statement with the correct person, A-F. Write the correct letter, A-F, in

boxes 4-10 on your answer sheet. NB You may use any letter more than once.

4. A pest invasion may seriously damage the banana industry.

5. The effect of fungal infection in soil is often long-lasting.

6. A commercial manufacturer gave up on breeding bananas for disease resistant species.

7. Banana disease may develop resistance to chemical sprays.

8. A banana disease has destroyed a large number of banana plantations.

9. Consumers would not accept genetically altered crop.

10. Lessons can be learned from bananas for other crops.

List of people

A Rodomiro Oritz

B David McLaughlin

C Emile Frison

D Ronald Romero

E Luadir Gasparotto

F Geoff Hawtin

Questions 11-13

Do the following statements agree with the information given in Reading Passage 1? In boxes 11-13 on your answer sheet, write

TRUE if the statement agrees with the information

FALSE if the statement contradicts the information

NOT GIVEN if there is no information on this

11. The banana is the oldest known fruit.

12. The Gros Michel is still being used as a commercial product.

13. Banana is the main food in some countries.

READING PASSAGE 2 Questions 14 – 26

You should spend about 20 minutes on Questions 14 – 26 which are based on Reading Passage 2 on the following pages.

Coastal Archaeology of Britain

The recognition of the wealth and diversity of England’s coastal archaeology has been The recognition of the wealth and diversity of England’s coastal archaeology has been one of the most important developments of recent years. Some elements of this enormous resource have long been known. The so-called ‘submerged forests’ off the coasts of England, sometimes with clear evidence of human activity, had attracted the interest of antiquarians since at least the eighteenth century, but serious and systematic attention has been given to the archaeological potential of the coast only since the early 1980s.

It is possible to trace a variety of causes for this concentration of effort and interest. In the 1980s and 1990s scientific research into climate change and its environmental impact spilled over into a much broader public debate as awareness of these issues grew; the prospect of rising sea levels over the next century, and their impact on current coastal environments, has been a particular focus for concern. At the same time archaeologists were beginning to recognise that the destruction caused by natural processes of coastal erosion and by human activity was having an increasing impact on the archaeological resource of the coast.

The dominant process affecting the physical form of England in the post-glacial period has been the rise in the altitude of sea level relative to the land, as the glaciers melted and the Iandmass re-adjusted. The encroachment of the sea, the loss of huge areas of land now under the North Sea and the English Channel, and especially the loss of the land bridge between England and France, which finally made Britain an island, must have been immensely significant factors in the lives of our pre-historic ancestors. Yet the way in which prehistoric communities adjusted to these environmental changes has seldom been a major theme in discussions of the period. One factor contributing to this has been that, although the rise in relative sea level is comparatively well documented, we know little about the constant reconfiguration of the coastline. This was affected by many processes, mostly quite localised, which have not yet been adequately researched. The detailed reconstruction of coastline histories and the changing environments available for human use will be an important theme for future research.

So great has been the rise in sea level and the consequent regression of the coast that much of the archaeological evidence now exposed in the coastal zone, whether being eroded or exposed as a buried land surface, is derived from what was originally terrestrial occupation. Its current location in the coastal zone is the product of later

unrelated processes, and it can tell us little about past adaptation to the sea. Estimates unrelated processes, and it can tell us little about past adaptation to the sea. Estimates of its significance will need to be made in the context of other related evidence from dry land sites. Nevertheless, its physical environment means that preserva-tion is often excellent, for example in the case of the Neolithic structure excavated at the Stumble in Essex.

In some cases these buried land surfaces do contain evidence for human exploitation of what was a coastal environment, and elsewhere along the modern coast there is similar evidence. Where the evidence does relate to past human exploitation of the resources and the opportunities offered by the sea and the coast, it is both diverse and as yet little understood. We are not yet in a position to make even preliminary estimates of answers to such fundamental questions as the extent to which the sea and the coast affected human life in the past, what percentage of the population at any time lived within reach of the sea, or whether human settlements in coastal environments showed a dis-tinct character from those inland.

The most striking evidence for use of the sea is in the form of boats, yet we still have much to learn about their production and use. Most of the known wrecks around our coast are not unexpectedly of post-medieval date, and offer an unparalleled opportunity for research, which has as yet been little used. The prehistoric sewn-plank boats such as those from the Humber estuary and Dover all seem to belong to the second millennium BC; after this there is a gap in the record of a millen-nium, which cannot yet be explained, before boats reappear, but built using a very different technology. Boatbuilding must have been an extremely important activity around much of our coast, yet we know almost nothing about it. Boats were some of the most complex artefacts produced by pre-modern societies, and further research on their production and use make an important contribution to our understanding of past attitudes to technology and technological change.

Boats needed landing places, yet here again our knowledge is very patchy. In many cases the natural shores and beaches would have sufficed, leaving little or no archaeological trace, but especially in later periods, many ports and harbours, as well as smaller faculties such as quays, wharves, and jetties, were built. Despite a growth of interest in the waterfront archaeology of some of our more important Roman and medieval towns, very little attention has been paid to the multitude of smaller landing places. Redevelopment of harbour sites and other development and natural pres-sures along the coast are subjecting these important locations to unprecedented threats, yet few surveys of such sites have been undertaken.

One of the most important revelations of recent research has been the extent of One of the most important revelations of recent research has been the extent of industrial activity along the coast. Fishing and salt production are among the better documented activities, but even here our knowledge is patchy. Many forms of fishing will leave little archaeological trace, and one of the surprises of recent survey has been the extent of past investment in facilities for procuring fish and shellfish. Elaborate wooden fish weirs, often of considerable extent and responsive to aerial photography in shallow water, have been identified in areas such as Essex and the Severn estuary. The production of salt, especially in the late Iron Age and early Roman periods, has been recognised for some time, especially in the Thames estuary and around the Solent and Poole Harbour, but the reasons for the decline of that industry and the nature of later coastal salt working are much less well understood. Other industries were also located along the coast, either because the raw materials outcropped there or for ease of working and transport: mineral resources such as sand, gravel, stone, coal, ironstone, and alum were all exploited. These industries are poorly docu-mented, but their remains are sometimes extensive and striking

Some appreciation of the variety and importance of the archaeological remains preserved in the coastal zone, albeit only in preliminary form, can thus be gained from recent work, but the complexity of the problem of managing that resource is also being realised. The problem arises not only from the scale and variety of the archaeological remains, but also from two other sources: the very varied natural and human threats to the resource, and the complex web of organisations with authority over, or interests in, the coastal zone. Human threats include the redevelopment of his-toric towns and old dockland areas, and the increased importance of the coast for the leisure and tourism industries, resulting in pressure for the increased provision of facilities such as marinas. The larger size of ferries has also caused an increase in the damage caused by their wash to fragile deposits in the intertidal zone. The most significant natural threat is the predicted rise in sea level over the next century, especially in the south and east of England. Its impact on archaeology is not easy to predict, and though it is likely to be highly localised, it will be at a scale much larger than that of most archaeological sites. Thus protecting one site may simply result in transposing the threat to a point further along the coast. The management of the archaeological remains will have to be considered in a much longer time scale and a much wider geographical scale than is common in the case of dry land sites, and this will pose a serious challenge for archaeologists.

Questions 14-16

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C or D. Write answers in boxes 14-16 on your sheet.

14. What has caused public interest in coastal archaeology in recent years?

A. The rapid development of England’s coastal archaeology

B. The rising awareness of climate change

C. The discovery of an underwater forest

D. The systematic research conducted on coastal archaeological findings

15. What does the passage say about the evidence of boats?

A. There’s enough knowledge of the boat building technology of the pre-historic people.

B. Many of the boats discovered were found in harbours.

C. The use of boats had not been recorded for a thousand years.

D. Boats were first used for fishing.

16. What can be discovered from the air?

A. Salt mines

B. Roman towns

C. Harbours

D. Fisheries

QUESTIONS 17-23

Do the following statements agree with the information given in Passage 2? write

TRUE if the statement agrees with the information

FALSE if the statement contradicts the information

NOT GIVEN if there is no information on this

17 . England lost much of its land after the Ice Age due to the rising sea level.

18 . The coastline of England has changed periodically.

19 . Coastal archaeological evidence may be well-protected by sea water.

20 . The design of boats used by pre-modem people was very simple.

21 . Similar boats were also discovered in many other European countries.

22 . There are few documents relating to mineral exploitation.

23 . Large passenger boats are causing increasing damage to the seashore.

Questions 24-26

Choose THREE letters from A-G. Write your answer in boxes 24-26 on your answer sheet. Which THREE of the following statements are mentioned in the passage?

A How coastal archaeology was originally discovered.

B It is difficult to understand how many people lived close to the sea.

C How much the prehistoric communities understand the climate change.

D Our knowledge of boat evidence is limited.

E Some fishing grounds were converted to ports.

F Human development threatens the archaeological remains.

G Coastal archaeology will become more important in the future.

READING PASSAGE 3 Questions 27 – 40

You should spend about 20 minutes on Questions 27 – 40 which are based on Reading Passage 3 below.

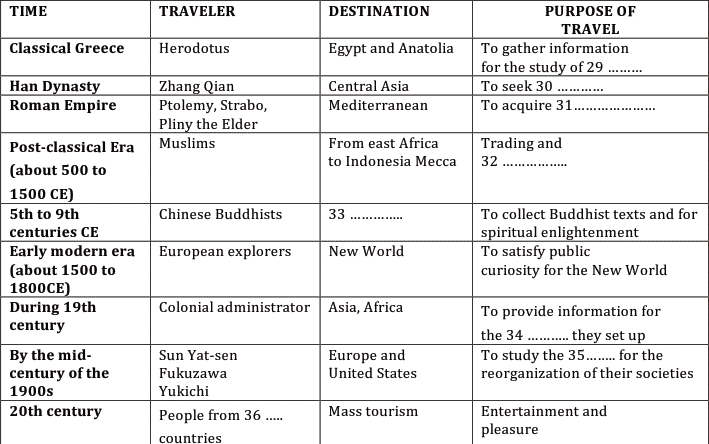

Travel Books

There are many reasons why individuals have traveled beyond their own societies. Some travelers may have simply desired to satisfy curiosity about the larger world. Until recent times, however, did travelers start their journey for reasons other than mere curiosity. While the travelers’ accounts give much valuable information on these foreign lands and provide a window for the understanding of the local cultures and histories,

they are also a mirror to the travelers themselves, for these accounts help them to have a better understanding of themselves.

Records of foreign travel appeared soon after the invention of writing, and fragmentary travel accounts appeared in both Mesopotamia and Egypt in ancient times. After the formation of large, imperial states in the classical world, travel accounts emerged as a prominent literary genre in many lands, and they held especially strong appeal for rulers desiring useful knowledge about their realms. The Greek historian Herodotus reported on his travels in Egypt and Anatolia in researching the history of the Persian wars. The Chinese envoy Zhang Qian described much of central Asia as far west as Bactria (modern-day Afghanistan) on the basis of travels undertaken in the first century BCE while searching for allies for the Han dynasty. Hellenistic and Roman geographers such as Ptolemy, Strabo, and Pliny the Elder relied on their own travels through much of the Mediterranean world as well as reports of other travelers to compile vast compendia of geographical knowledge.

During the postclassical era (about 500 to 1500 CE), trade and pilgrimage emerged as major incentives for travel to foreign lands. Muslim merchants sought trading opportunities throughout much of the eastern hemisphere. They described lands, peoples, and commercial products of the Indian Ocean basin from east Africa to Indonesia, and they supplied the first written accounts of societies in Sub-Saharan West Africa. While merchants set out in search of trade and profit, devout Muslims traveled as pilgrims to Mecca to make their hajj and visit the holy sites of Islam. Since the prophet Muhammad’s original pilgrimage to Mecca, untold millions of Muslims have followed his example, and thousands of hajj accounts have related their experiences. East Asian travelers were not quite so prominent as Muslims during the postclassical era, but they too followed many of the highways and sea lanes of the eastern hemisphere. Chinese merchants frequently visited southeast Asia and India, occasionally venturing even to east Africa, and devout East Asian Buddhists undertook distant pilgrimages. Between the 5th and 9th centuries CE, hundreds and possibly even thousands of Chinese Buddhists traveled to India to study with Buddhist teachers, collect sacred texts, and visit holy sites. Written accounts recorded the experiences of many pilgrims, such as Faxian, Xuanzang, and Yijing. Though not so numerous as the Chinese pilgrims, Buddhists from Japan, Korea, and other lands also ventured abroad in the interests of spiritual enlightenment.

Medieval Europeans did not hit the roads in such large numbers as their Muslim and East Asian counterparts during the early part of the postclassical era, although gradually increasing crowds of Christian pilgrims flowed to Jerusalem, Rome, Santiago de- Compostela (in northern Spain), and other sites. After the 12th century, however, merchants, pilgrims, and missionaries from medieval Europe traveled widely and left numerous travel accounts, of which Marco Polo’s description of his travels and sojourn in China is the best known. As they became familiar with the larger world of the eastern hemisphere—-and the profitable commercial opportunities that it offered—European people worked to find new and more direct routes to Asian and African markets. Their efforts took them not only to all parts of the eastern hemisphere, but eventually to the Americas and Oceania as well.

If Muslim and Chinese peoples dominated travel and travel writing in postclassical times, European explorers, conquerors, merchants, and missionaries took center stage during the early modern era (about 1500 to 1800 CE). By no means did Muslim and Chinese travel come to a halt in early modern times. But European peoples ventured to the distant corners of the globe, and European printing presses churned out thousands of travel accounts that described foreign lands and peoples for a reading public with an apparently insatiable appetite for news about the larger world. The volume of travel literature was so great that several editors, including Giambattista Ramusio, Richard Hakluyt, Theodore de Bry, and Samuel Purchas, assembled numerous travel accounts and made them available in enormous published collections.

During the 19th century, European travelers made their way to the interior regions of Africa and the Americas, generating a fresh round of travel writing as they did so. Meanwhile, European colonial administrators devoted numerous writings to the societies of their colonial subjects, particularly in Asian and African colonies they established. By midcentury, attention was flowing also in the other direction. Painfully aware of the military and technological prowess of European and Euro-American societies, Asian travelers in particular visited Europe and the United States in hopes of discovering principles useful for the reorganisation of their own societies. Among the most prominent of these travelers who made extensive use of their overseas observations and experiences in their own writings were the Japanese reformer Fukuzawa Yukichi and the Chinese revolutionary Sun Yat-sen.

With the development of inexpensive and reliable means of mass transport, the 20th century witnessed explosions both in the frequency of long-distance travel and in the volume of travel writing. While a great deal of travel took place for reasons of business, administration, diplomacy, pilgrimage, and missionary work, as in ages past, increasingly effective modes of mass transport made it possible for new kinds of travel to flourish. The most distinctive of them was mass tourism, which emerged as a major form of consumption for individuals living in the world’s wealthy societies. Tourism enabled consumers to get away from home to see the sights in Rome, take a cruise through the Caribbean, walk the Great Wall of China, visit some wineries in Bordeaux, or go on safari

in Kenya. A peculiar variant of the travel account arose to meet the needs of these tourists: the guidebook, which offered advice on food, lodging, shopping, local customs, and all the sights that visitors should not miss seeing. Tourism has had a massive economic impact throughout the world, but other new forms of travel have also had considerable influence in contemporary times.

(peoples – The human beings of a particular nation , community or ethnic group) Anywhere else the use of the word peoples is wrong

Questions 27-28

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C or D. Write your answers in boxes 27-28 on your answer sheet.

27 . What were most people traveling for in the early days?

A Studying their own cultures

B Business

C Knowing other people and places better

D Writing travel books

28 . Why did the author say writing travel books is also “a mirror” for travelers themselves?

A Because travelers record their own experiences.

B Because travelers reflect upon their own society and life.

C Because it increases knowledge of foreign cultures.

D Because it is related to the development of human society.

Questions 29-36

Complete the table below. Write NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from passage 3

Questions 37-40

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C or D. Write your answers in boxes 37-40

37 . Why were the imperial rulers especially interested in these travel stories?

A Reading travel stories was a popular pastime.

B The accounts are often truthful rather than fictional.

C Travel books played an important role in literature.

D They desired knowledge of their empire.

38 .Who were the largest group to record their spiritual trip during the postclassical era?

A Muslim traders

B Muslim pilgrims

C Chinese Buddhists

D Indian Buddhist teachers

39 .During the early modern era, a large number of travel books were published to

A Meet the public’s interest.

B Explore new business opportunities.

C Encourage trips to the new world.

D Record the larger world.

40 .What’s the main theme of the passage?

A The production of travel books

B The literary status of travel books

C The historical significance of travel books

D The development of travel books

Academic reading practice test 37 Going bananas , Travel Books , Coastal Archaeology of Britain latest exam actual tests with answer Academic reading practice test 37 Going bananas , Travel Books , Coastal Archaeology of Britain latest exam actual tests with answer Academic reading practice test 37 Going bananas , Travel Books , Coastal Archaeology of Britain latest exam actual tests with answer Academic reading practice test 37 Going bananas , Travel Books , Coastal Archaeology of Britain latest exam actual tests with answer Academic reading practice test 37 Going bananas , Travel Books , Coastal Archaeology of Britain latest exam actual tests with answer Academic reading practice test 37 Going bananas , Travel Books , Coastal Archaeology of Britain latest exam actual tests with answer Academic reading practice test 37 Going bananas , Travel Books , Coastal Archaeology of Britain latest exam actual tests with answer Academic reading practice test 37 Going bananas , Travel Books , Coastal Archaeology of Britain latest exam actual tests with answer Academic reading practice test 37 Going bananas , Travel Books , Coastal Archaeology of Britain latest exam actual tests with answer Academic reading practice test 37 Going bananas , Travel Books , Coastal Archaeology of Britain latest exam actual tests with answer Academic reading practice test 37 Going bananas , Travel Books , Coastal Archaeology of Britain latest exam actual tests with answer Academic reading practice test 37 Going bananas , Travel Books , Coastal Archaeology of Britain latest exam actual tests with answer Academic reading practice test 37 Going bananas , Travel Books , Coastal Archaeology of Britain latest exam actual tests with answer Academic reading practice test 37 Going bananas , Travel Books , Coastal Archaeology of Britain latest exam actual tests with answer Academic reading practice test 37 Going bananas , Travel Books , Coastal Archaeology of Britain latest exam actual tests with answer Academic reading practice test 37 Going bananas , Travel Books , Coastal Archaeology of Britain latest exam actual tests with answer Academic reading practice test 37 Going bananas , Travel Books , Coastal Archaeology of Britain latest exam actual tests with answer Academic reading practice test 37 Going bananas , Travel Books , Coastal Archaeology of Britain latest exam actual tests with answer Academic reading practice test 37 Going bananas , Travel Books , Coastal Archaeology of Britain latest exam actual tests with answer Academic reading practice test 37 Going bananas , Travel Books , Coastal Archaeology of Britain latest exam actual tests with answerAcademic reading practice test 37 Going bananas , Travel Books , Coastal Archaeology of Britain latest exam actual tests with answerAcademic reading practice test 37 Going bananas , Travel Books , Coastal Archaeology of Britain latest exam actual tests with answerAcademic reading practice test 37 Going bananas , Travel Books , Coastal Archaeology of Britain latest exam actual tests with answerAcademic reading practice test 37 Going bananas , Travel Books , Coastal Archaeology of Britain latest exam actual tests with answer

Pages Content